Evidence-based medicine. Who decides admissibility? Part 3: Exculpatory evidence and the effect of treatment.

The question in the title is rhetorical and ironic. It was only meant to bring out the idea that you don’t get to call your own data, “evidence” without justification. To bring out the requirements for meaningfull data, I have discussed procedures in the legal system. Courts of law have judges and rules of evidence to decide admissibility, of evidence, cross-examination to determine the reliablity of the evidence and juries to decide whether the evidence is compelling. The rules in medicine — if they exist — need work. The goal, then, is to see if the statutes and behavior in a court of law can help us deal with the crisis in nutrition.

The current standards on evidence in the law, derived from Daubert, emphasize relevance, reliability and the analysis of error. As indicated in my previous posts, in Daubert, the court invoked Karl Popper who maintained that a necessary feature of scientific evidence is criterion was falsifiability. And generally, contradiction provides much stronger evidence for truth of a theory than consistency does.

Exculpatory Evidence, Brady v. Maryland.

To show that a nutrient or other agent causes an injury or disease requires various lines of evidence but even isolated counter examples can carry much weight. Authors are expected to produce conflicting data and to rebut it or describe its limitations. By analogy with conviction of a criminal defendant, the courts have ruled that exculpatory evidence must be presented in tests of guilt or innocence. Known as Brady material (not to be confused with Brady in gun control), any evidence that might be favorable to the defendant or any data that might negate their guilt or reduce their sentence, must be produced by the prosecution. In 1958, John Brady and his accomplice were convicted of murder. They were tried separately. Both were found guilty and sentenced to death. Although they had both participated in the crime, it turned out that the accomplice had committed the actual act of murder and had signed a confession. In Brady’s trial, however, the prosecution withheld the confession. The Maryland Court of Appeals affirmed the murder conviction but ordered a new hearing with respect to the punishment which was reduced to life imprisonment. The ruling was upheld by the Supreme Court and Brady’s sentence was ultimately commuted and he was pardoned.

By analogy, in the case at hand, Gu, et al. [1], claimed red meat as a risk for diabetes. The authors, however, did not cite “Brady material” shown in an increasingly familiar graphic (below).

The major decline in consumption of red meat in the United States has been accompanied by the dramatic increase in diabetes. I had actually made the point several years ago in a letter to the editor [2] in response to a paper that had presented a prior version of the same data [3]. and suggested risk for all kinds of problems. The authors dismissed this contradictory evidence in the figure by claiming that it was “ecological.” The evidence was not cited at all in the current case [1], behavior that is usually considered a violation of good scientific practice. In effect, their attempt to convict red meat of causing diabetes would not be admitted into evidence in a court of law.

Red Meat Causes Diabetes.

Gu, et al. [1] claimed that their study “supports current dietary recommendations for limiting consumption of red meat intake and emphasizes the importance of different alternative sources of protein for Type 2 diabetes prevention.” The alternatives whose consumption was recommended were nuts, legumes and dairy. To most workers in the field, this sounds like apples and origins. These are not comparable sources of protein. In fact, what is recommended, in effect, will almost certainly increase carbohydrate at the expense of protein, a change that is unlikely to be beneficial or that at least has to have experimental benefit in the context of diabetes.

What about treatment?

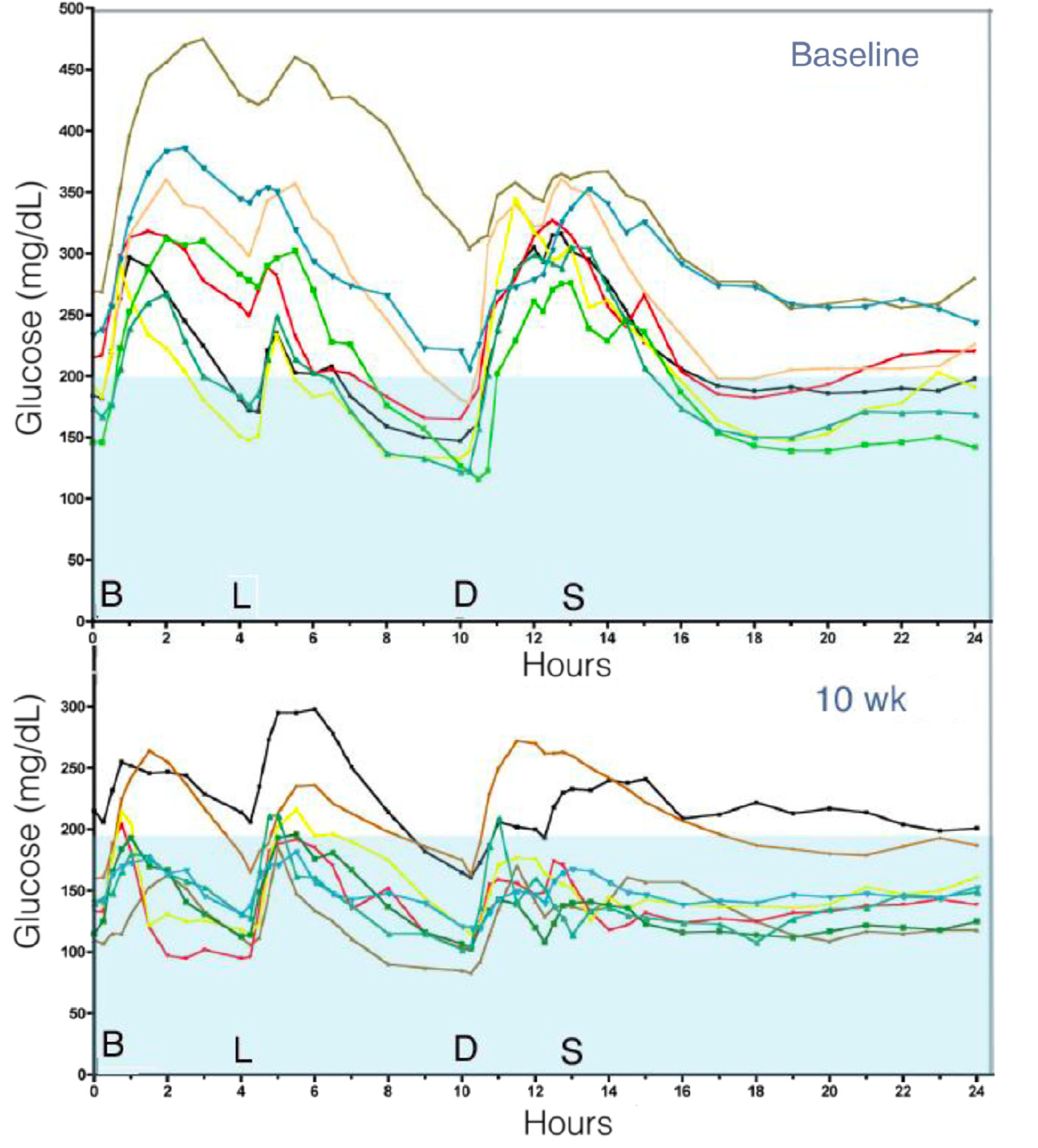

Type 2 diabetes is a disease of disruption of the glucose-insulin axis. We don’t really know the cause or the best method of prevention. We do know a good deal about treatment — carbohydrate restriction as the first approach provides the best evidence [4] — and it is generally assumed that the carbohydrate concentration participates, in some way, in the etiology of the disease. Replacing carbohydrate with protein is well studied. Numerous studies, show that lower carbohydrate, higher protein, even red meat protein improves the symptoms of disease. Nuttall and Gannon have done several careful studies on carbohydrate reduction and its replacement with protein [5, 6, 7]. For example, Gannon, et al. tested the response of 12 men to a LoBag30 (low bioavailable glucose) diet with high protein (30%). After 10 weeks, dramatic reductions in blood glucose compared to their prior 15% protein were found [5]. Hemoglobin A1c was reduced from 10% at the beginning of the 10 week period and linearly decreased to 7.5 % by the end. Everybody in the study improved.

Daily response of 12 men to a 10 week LoBag30 (low bioavailable glucose) diet with high protein (30%).

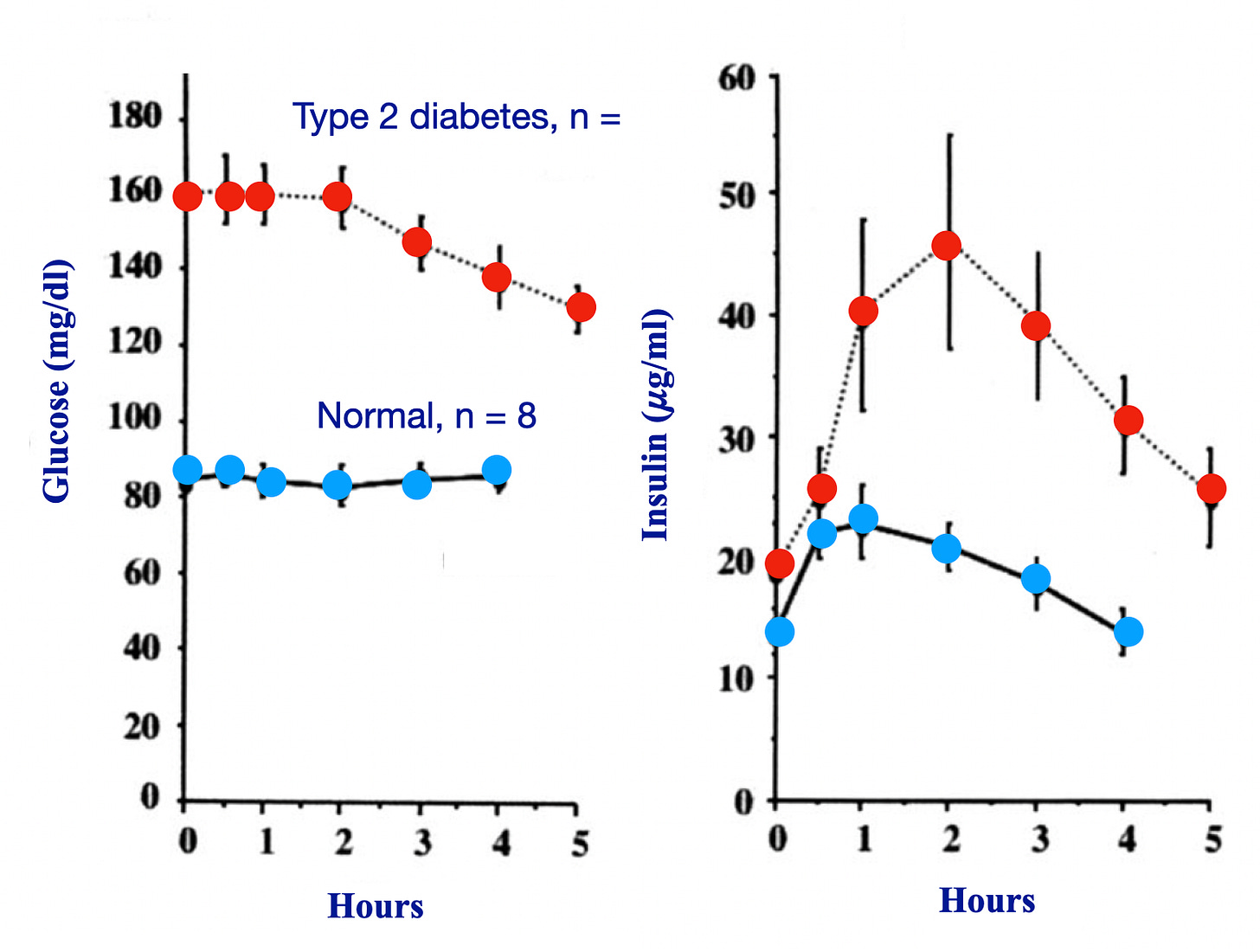

Cutting to the chase, in 1984, Nuttall and Gannon studied the response to ingestion of 50 grams of lean beef in 7 subjects with type 2 diabetes, and 8 normal subjects [7]. Normal subjects showed no change in blood glucose concentration over 4 hours. In distinction, the subjects with type 2 diabetes showed a decrease over the 5 hours of that study. The addition of lean beef had a relatively slight increase in insulin concentration in the normal subjects but a dramatic increase in the subjects with diabetes.

Response to 50 g. of lean beef in 8 normal subjects and 7 subjects with type 2 diabetes. Redrawn from reference [6].

Different variations of protocol establish that the substitution of protein (containg a renge of red meat) will reliably improve type 2 diabetes. In fact, higher protein and lower carbohydrate is a feature of recent studies that appear to put diabetes in remission.

What would it mean if red meat were a risk for diabetes? If the conslusion from Gu, et al. were accurate, increasing red meat in your diet would increase your risk. Once you had diabetes, however, further addition of red meat will lead to improvement. Of course, if you were replacing plant-based food and wanted to maintain the level of protein, you would also increase the carbohydrate intake. This doesn’t make sense but is important because it is recognized that it would be hard to make an ethical experiment testing causes of diabetes. In other words, the effect of macronutrients on risk of occurence suggests testing them against the nutrients as treatment.

Is it ethical?

The case against red meat would never make it in a court of law. The failure to introduce Brady material is an important fault. Were these studies not known to the authors. If they were, would the gate-keepers — editors and reviewers — have admitted this into evidence. The data in Figure 1, in fact, were known to the authors. Why did they not include it? The limitations of the legal analogy appear in the question of motive. In a court of law, the breach of good practice can be taken as evidence of the mens rea, the motivation of the party. In controversy in science, though, we have to assume here that this oversight was done in good conscience. It is nonetheless a serious fault. Before the Brady ruling, failure to disclose exculpatory evidence was considered prejudicial if the material had been withheld intentionally. In Brady, the Supreme Court has held that any concealment of exculpatory evidence, intended or otherwise, will compromise the inclusion of proposed evidence of guilt. and may be suppressed if there is whether or not the prosecution knew that they had such material. the Prosecution has a constitutional duty to disclose Brady material and is expected to seek it. State courts have ruled that the police cannot even “look the other way.”

Contrary to the usual disclaimers, Gu, et al. are giving medical advice. Given the linitations of their study as brought out by the legal analogy, is it really ethical to encourage nuts and legumes in place of red meat?

Gu, X, Drouin-Chartier, J-P, Sack, FM, Frank, FB, Rosner, B. Willett, WC. Red meat intake and risk of type 2 diabetes in a prospective cohort study of United States females and males. Am. J. Clin. Nutr.. (2023) 118, 1153-1163. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajcnut.2023.08.021.

Feinman, RD, Red Meat and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. JAMA Internal Medicine (2014) 174, 646-647. DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12869.

Pan A, Sun, Bernstein AM, Manson JE, Willett WC, Hu FB. Changes in red meat consumption and subsequent risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: three cohorts of US men and women. JAMA Intern Med. (2013) 173, 1328-1335. DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6633.

Feinman RD, et al., Dietary carbohydrate restriction as the first approach in diabetes management: Critical review and evidence base, Nutrition (2014) , http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2014.06.011.

Gannon, M.C., Hoover, H. and Nuttall, F.Q. Further Decrease in Glycated Hemoglobin Following Ingestion of a LoBAG30 Diet for 10 Weeks Compared to 5 Weeks in People with Untreated Type 2 Diabetes. Nutrition and Metabolism (London) (2010) 7, 64. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1743-7075-7-64.

Gannon MC, Nuttall FQ. Control of blood glucose in type 2 diabetes without weight loss by modification of diet composition. Nutr Metab (Lond) (2006) 3:16. DOI: 10.1186/1743-7075-3-16.

Nuttall FQ, Mooradian AD, Gannon MC, Billington C, Krezowski, PA: Effect of protein ingestion on the glucose and insulin response to a standardized oral glucose load. Diab Care (1984) 7 465–470. DOI: 10.2337/diacare.7.5.465.